Chapter 5

The Choir and the Damned

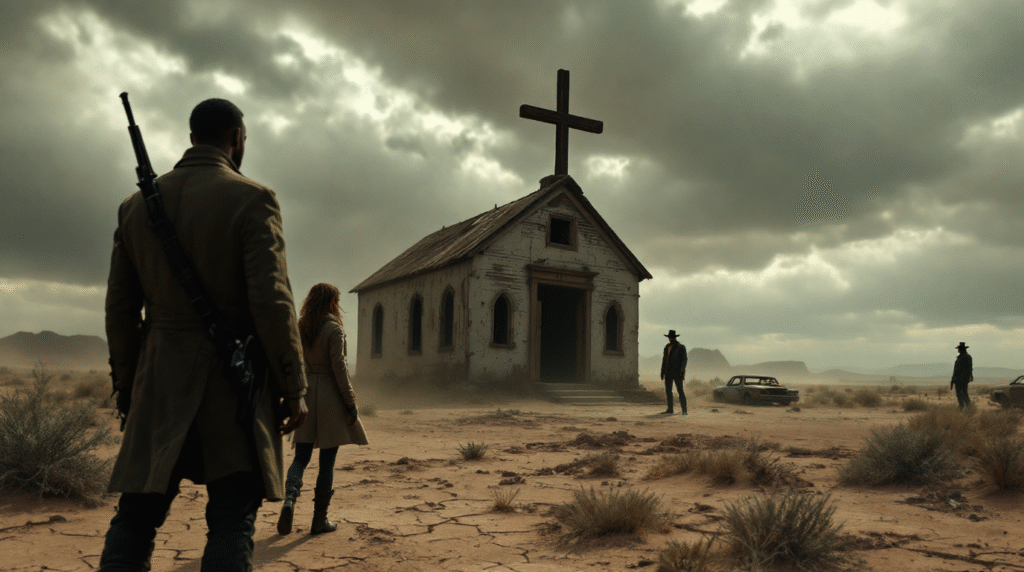

The sun was high, but the church felt darker than before.

It loomed in daylight like it had something to hide — the sagging cross now casting a crooked shadow across the parking lot. What little charm it once had had soured, replaced with a sterility that made the skin itch. The air was too still. No birds. No wind. Just that kind of silence that squeezes the lungs and makes you check your pockets for a weapon you already know you brought. It was the kind of quiet that remembered violence.

Mac stepped out of the Power Wagon and adjusted the brim of his hat. The sun caught the edge of his sunglasses, but the glare in his eyes was all his own. “Tell me this place doesn’t smell cleaner than it did two nights ago.”

Baz was already scanning the perimeter, one hand resting on the knife at her hip. Her nose wrinkled like she’d smelled something foul. “Bleach,” she muttered. “Too much of it. And too recent.”

Silas didn’t answer. His eyes were locked on the front door, slightly ajar, swaying like it had something to say but couldn’t decide how to start. Something about it gnawed at him, like the memory of a dream he couldn’t place.

They approached in a triangle. Baz on point, Mac to the rear, Silas flanking. No words exchanged — just muscle memory, old instincts slotting into place like rounds in a chamber.

Inside, the pews were immaculate. Polished even. Hymnals re-aligned. The scent of ammonia was thick enough to taste, clinging to the back of the throat, acidic and artificial.

Mac spoke low. “This ain’t cleaning. This is erasure.”

Silas nodded slowly, his boots echoing as he moved toward the altar. Each step sounded too loud, like they were intruding on something ancient. Something watching.

“Eyes up,” Baz said from near the pulpit. “Something’s changed.”

She pointed to the organ.

Every key was pressed down — held in place by strips of torn sheet music, wedged so deliberately that it could only be a message.

“Same pattern as before?” Mac asked.

Baz shook her head. “Worse. It’s not random. It’s recursive. A loop. Whoever did this… they want someone to understand.”

Silas stepped closer. The organ had been scrubbed. But the polish missed a spot. Etched faintly into the wood, just above the keys, were the words:

*”They were warned.”

The choir director lived in a faded blue ranch house two blocks from the church — a sagging porch, sun-blistered paint, and wind chimes that hadn’t moved all morning. A rusted Buick sat in the gravel driveway, tires weather-cracked and tired. The screen door was missing. That felt appropriate.

Mac knocked once. Not polite. Not aggressive. Just enough to say they weren’t going away.

A pause.

Then the door creaked open.

Cora Bellweather looked smaller than she had at the church, stripped of her pressed blazer and righteous posture. Her hair was damp, pulled back in a rushed bun. The neckline of her sweatshirt was frayed, and her eyes — eyes that once brimmed with community pep and rehearsed concern — now darted like trapped things.

“Detective. Sheriff.” Her voice was low. Hoarse. “I told you everything I knew.”

Mac didn’t blink. “We came back for the lies.”

She stiffened but didn’t move to close the door. Baz stepped forward, hands empty but stance sharp.

“We’re not here for drama, Cora,” Baz said. “We’re here because the Franklin girl is still missing, and someone scrubbed that church like they were afraid of what we’d find.”

Cora glanced past them, into the street, like maybe salvation was out there disguised as a nosy neighbor.

Silas spoke, and his voice had that quiet gravity that made people listen even if they didn’t want to. “We’re not asking. You knew there was a rehearsal scheduled. You told us otherwise. That wasn’t a mistake. That was a cover.”

“I…” Her lip trembled. She looked at Baz, then away. “I didn’t know what would happen. I swear.”

Baz stepped in close. “But you knew something.”

Cora’s mouth opened. Closed. Her jaw flexed like she was chewing glass.

“It wasn’t supposed to matter,” she whispered. “She wanted to sing. She said it helped the nightmares.”

Mac tilted his head. “Who’s ‘she’?”

Cora blinked like she’d just realized she’d said too much.

“I didn’t know her name,” she said too quickly. “She wasn’t in the choir. Just… a visitor. Said she knew the Franklin girl. Said music helped her remember who she was.”

Silas took a slow breath. “And you let her in?”

“I didn’t think—she had keys. She knew the alarm code. I assumed—God help me, I assumed someone else approved it. I just wanted to go home that night.”

Mac’s hands clenched at his sides. “You saw her face?”

Cora hesitated. “No.”

Baz’s voice was flat. “Try again.”

“She wore a veil,” Cora whispered. “Not like a bride. Thinner. Like something from a stage costume. I asked why. She said she had scarring. Said the girl understood.”

“What girl?” Silas said, his voice tight.

Cora’s eyes filled, but no tears fell.

“She was already there. Sitting on the altar steps. Humming. Rocking back and forth. She looked… wrong. Her eyes were wrong. But I—” her breath hitched. “I thought maybe it was just the lighting. Or grief. I didn’t want to cause trouble.”

Baz stared at her. “And then what?”

“They sang. Just once. A strange hymn. Not one we keep in the books.” She paused. “It didn’t rhyme.”

Mac’s eyes narrowed. “And then?”

“When I came back… they were gone.”

The silence that followed wasn’t just awkward — it was judgmental.

“You never told anyone?” Silas asked.

Cora shook her head slowly. “By the time I understood it was real, I was already lying. And by then, the fear had its claws in me.”

Baz turned to leave first but paused in the doorway.

“Next time you feel fear’s claws,” she said without turning, “think about what it feels like to wake up in a room where no one’s coming to help you.”

They left Cora standing in the doorway, small and shrinking — another witness who let the devil in because he knocked politely.

The sheriff’s station breathed a different kind of silence. Not the watchful, ritual hush of the church — this was the sound of paper hiding truths and dust collecting on answers no one wanted to find.

Mac dropped the evidence envelope on the warped conference table like it owed him money. The photo of the organ slipped halfway out, sheet music edge curling like a tongue trying to speak.

Baz paced. Not aimless — measured. Like she was trying to wear a groove into the tile with the soles of her boots, grinding her anxiety into the ground until it flattened into focus.

“She knew,” Baz muttered. “Not everything. But enough to stop it. To stall it. She did nothing.”

“She’s scared,” Silas said quietly, still staring at the photo. “Scared people do selfish things. Or nothing at all.”

Baz shot him a look. “So is the girl. And she doesn’t get a choice.”

Mac didn’t interrupt. He sat in his chair, boots planted wide, hands steepled just under his chin. He’d gone still — that unnerving kind of stillness that said he was more than listening. He was calculating the weight of each word.

“Something doesn’t add up,” Mac said finally. “This veiled woman. Keys. Alarm code. That’s not improvisation. That’s planning. Infrastructure.”

Silas nodded slowly. “Inside job?”

“Or someone with legacy access,” Mac replied. “Old member. Donor. Ex-staff. Someone whose name still gets through a door even if nobody remembers their face.”

Baz crossed her arms. “You think this is local?”

Mac exhaled through his nose, the breath rough like sandpaper. “I think someone’s playing long games in short time. And they’re not afraid to use what people fear most — faith, memory… children.”

The station lights buzzed overhead like they were tired of illuminating bad news.

Just then, Deputy Walker eased the door open with the kind of face that usually preceded an apology. Instead, he held out a plastic bag with gloved hands.

Inside was a cassette tape — unlabeled. Cracked case. The kind you find in glove boxes and basements. The kind that shouldn’t exist anymore.

“Where’d you get this?” Mac asked, not yet reaching for it.

Walker swallowed. “It was left in the church mailbox. Addressed to you.”

Mac took it carefully. The plastic felt cold, colder than it should have, like it had been waiting.

“Cassette player?”

Silas stood. “I got one in the truck. Came with the Power Wagon.”

Baz was already moving. “Then let’s find out what kind of song this is.”

The Power Wagon creaked as they settled in. Mac leaned against the hood, arms folded, while Silas fumbled with the deck — a stubborn artifact wired into the dash like an afterthought that refused to be forgotten.

Baz slid into the passenger seat. The cab smelled like oil, leather, and heat. Familiar. Grounding.

Silas inserted the tape.

For a second, nothing.

Then the gears whirred, the tape clicked, and a thin hiss filled the cab — the kind of static that sounds too alive. Then:

“Brothers and sisters…”

A voice. Male. Middle-aged. Hollow, but steady — unnervingly steady. It wrapped around the words like velvet around a dagger.

“We gather not in defiance, but in remembrance. Not to mourn the fallen, but to awaken the sleeping. For the old songs have failed us. The sanctioned melodies have gone cold.”

Baz tensed. Her spine locked straight. Her breath slowed.

“There is no redemption in silence. There is no salvation in hymns written by cowards.”

“She sang. And in that singing, the door opened. Not wide, no — but wide enough. They heard. They answered.”

Static stuttered.

Then — voices.

Not screaming. Not crying.

Singing.

A hymn.

But it wasn’t a song. It was a spiral. A dirge with no beginning and no resolution. Slightly off-key — each voice perhaps a quarter-tone low, just enough to stir the lizard brain into flinching. Like a prayer whispered into a coffin.

Baz covered her ears halfway through. “Turn it off,” she said. Quietly. But no one moved.

Silas sat frozen, jaw clenched. There were words inside the song. Or behind it. Or beneath it. Words that bypassed language and aimed for marrow.

Mac reached forward and hit the eject button.

The tape stopped.

The silence that followed wasn’t relief.

It was contamination.

Mac pocketed the cassette and stepped out of the truck.

“I want a full report on every former staff member at that church,” he said. “Anyone with keys. Donors. Choir alumni. I want addresses. Arrest records. Hell, I want Sunday School rosters from ’92.”

Baz climbed out after him, voice low and raw. “You think it’s local?”

“I think this town’s got rot in the foundation,” Mac said, lighting a cigarette with a snap of his Zippo. “And someone’s finally figured out how to make it sing.”

Baz sat at the long table in the back office, surrounded by half-built timelines and hand-scribbled notes. A portable cassette deck — ancient, yellowed plastic, taped speaker — hummed at her elbow.

She replayed the tape.

Fast-forwarded past the sermon and the song. Past the static.

Then: silence.

Then…

“Is this thing… recording?”

A girl’s voice. Shaky. Young.

Alive.

Baz froze. Her pencil dropped from her hand, forgotten.

“I don’t know how long I’ve been here. Days, maybe. They keep the lights off. They say singing helps me ‘stay in the light.’ But it hurts now. The songs… they change when I sleep.”

“If anyone finds this, my name is Sarah Franklin. I was at the church that night. I… I think I sang something wrong.”

“Please. Please don’t let them make me sing again.”

Then static.

Then nothing.

No outro. No click.

Just the silence of a space that had heard too much.

Baz stared at the deck. Her breath came shallow now. Something in her chest twisted.

She stood. Took the tape. Her boots were moving before her brain caught up.

“Silas!” she shouted down the hallway. “Mac!”

Footsteps pounded behind doors and around corners.

She didn’t wait.

Her voice carried the weight of confirmation.

“She’s alive.”